Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

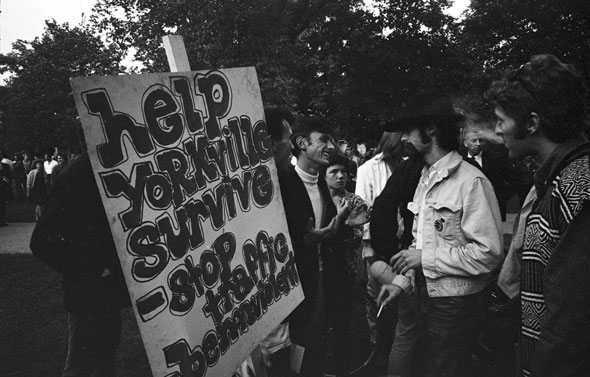

Yorkville in the 1960sYorkville is a section of urban Toronto that was the centre of the counterculture in the mid-1960s. It takes its name from Yorkville Avenue, an east-west street which runs between Avenue Road and Yonge Street, but as a district, its boundaries were roughly Bloor Street on the south, Davenport Road. to the north, Yonge Street to the east, and Avenue Road to the west. In addition to Yorkville Avenue itself, Cumberland Street, Hazelton Avenue, Scollard Street, and Bellair Street are part of the Yorkville district. An area of small Victorian-era houses at the time, Yorkville had become a magnet for the Beatnik subculture of the late 1950s and early 1960s because of its cheap rents, inexpensive rooming-houses, and small, intimate coffee houses where poetry and jazz were shared. When the “hippie” counterculture of the mid-1960s arrived, with its thousands of young people on the move from coast to coast to coast, Yorkville became a thriving haven for folk and rock music, peace activism, “free love” sexual experimentation, and a lifestyle of sharing, community-building, and brotherhood. A whole generation appeared to be uninterested in the conformity, consumerism, and boredom of the mainstream culture embraced by their parents. At least 40 clubs and coffee houses thrived in Yorkville and nightly featured musicians such as Joni Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot, Bruce Cockburn, Neil Young, Simon & Garfunkle, James Taylor, Tom Rush, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Carly Simon, Murray McLaughlin, Ian & Sylvia Tyson, Dan Hill, Lonnie Johnson, Richie Havens, The Staple Singers, and others who went on to have decades-long careers. Writers such as Leonard Cohen, Margaret Atwood, Gwendolyn MacEwen, and Dennis Lee honed their craft in front of Yorkville audiences receptive to their “underground” poetry. The names of many of the clubs are now part of the Yorkville legend and history: The Riverboat Coffee House, The Penny Farthing, the Mynah Bird, the Purple Onion, the Devil’s Den, El Patio, Borris’s, the Night Owl, Chez Monique, the Village Corner, and Flick. The Yorkville scene also spawned its own underground newspaper, Harbinger, which was co-edited by Hans Wetzel and David Bush and carried some political news along with drawings, rants, calendars of events, etc. Like Greenwich Village in New York City and Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, Yorkville in the 1960s revolved around “sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll,” but at first no hard drugs (like speed or heroin) were tolerated in the area by common consensus, and only the smoking of pot (cannabis) was noticeable because of its telltale odour. Later LSD entered the scene. The line-ups of young people waiting on the sidewalks to get into the clubs were themselves colourful and intriguing, with their long-hair and their sometimes outrageous (or at least unusual) clothing. In fact, these crowds attracted tourists every night who drove through Yorkville streets to see the “hippies”. The tourist influx became so massive that Yorkville’s counterculture became the first anti-car movement in Canada, with sit-ins and sleep-ins at City Hall and Queen’s Park in attempts to ban cars from Yorkville because of pollution and safety issues. A group called Digger House, organized by June Callwood and others, played a central role in these protests. A “love-in” at Queen’s Park to stop Yorkville traffic in 1967 brought out some 4,000 participants. The “City fathers” at the time mostly considered the Yorkville hippies as transient riff-raff and were eager to shut down the area. During the summer of 1967, there were three nights of public turmoil as police battled the hippies and tried to arrest as many as possible. Out of the turmoil, a spokesman arose: David DePoe, who was a member of Digger House and an employee of the Council of Young Canadians. DePoe valiantly attempted to reason with members of City Hall, including the city controller Allan Lamport, who had been the conservative mayor of Toronto during the 1950s. Lamport despised everything the hippies stood for – especially anti-materialism and the idea of sharing one’s goods with others. DePoe tried to convince Lamport and his colleagues that Yorkville was an important attempt to find an alternative style of living. The National Film Board made a documentary that included the confrontation between DePoe and Lamport, called “Flowers on a One-way Street”. Another NFB documentary shot in Yorkville during the mid-l960s was “Christopher’s Movie Matinee”. Of course, the films (along with on-going and widespread media coverage) increased the number of people flocking to Yorkville to participate or gawk. By autumn of 1967, Yorkville was attracting a new and unexpected contingent of mobile youth: very troubled young teens fleeing abusive home situations, or those who had fallen through the cracks of Canada’s social services and foster homes, or who been kicked out of high schools for various reasons. The resident Yorkville hippies tried their best, through Digger House and other Toronto charities, to provide basic care for these young outcasts who wanted basically to escape into hard drugs. But they had neither the training nor the resources to take on such problems. This new contingent was a factor in the demise of Yorkville, but there were other factors. By the late 1960s, there was also an escalation of biker gangs and violence in the area, along with the increased presence of hard drugs and pushers. A hepatitis scare (whether a rumour or not) also kept people away from the neighbourhood. But perhaps an even bigger contributor to the demise and downfall of the Yorkville scene was the impact of redevelopment in the area. Accompanying the planned expansion of the Bloor-Danforth subway system, developers began to buy up adjoining properties along the subway route, speculating on a wave of increased land-values and gentrification. One major developer named Richard Wookey bought up 70 houses in Yorkville and built Hazelton Lanes – an upscale shopping mall. Similarly, The Bay department store and Holt Renfrew replaced small, local retail shops that had sold tie-dye tee-shirts, rolling papers, health foods, etc. These developers eventually turned Yorkville into one of the most expensive shopping and residential areas in North America. So what happened to the Yorkville hippies? Some of them joined the “back-to-the-land” movement and worked on communal farms. Others enrolled in universities, having found inspiration for continuing their education. Some remained committed to music and opened other venues in Toronto and elsewhere. Others dropped the counterculture entirely and found work in “the system”. Some deepened their political involvement and became activists, if they weren”t already. All no doubt vividly recall their experience of the mid-1960s Yorkville scene. Related Reading/Viewing: Related Topics: This article is also available in French.

|

Connect with Connexions

|