Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

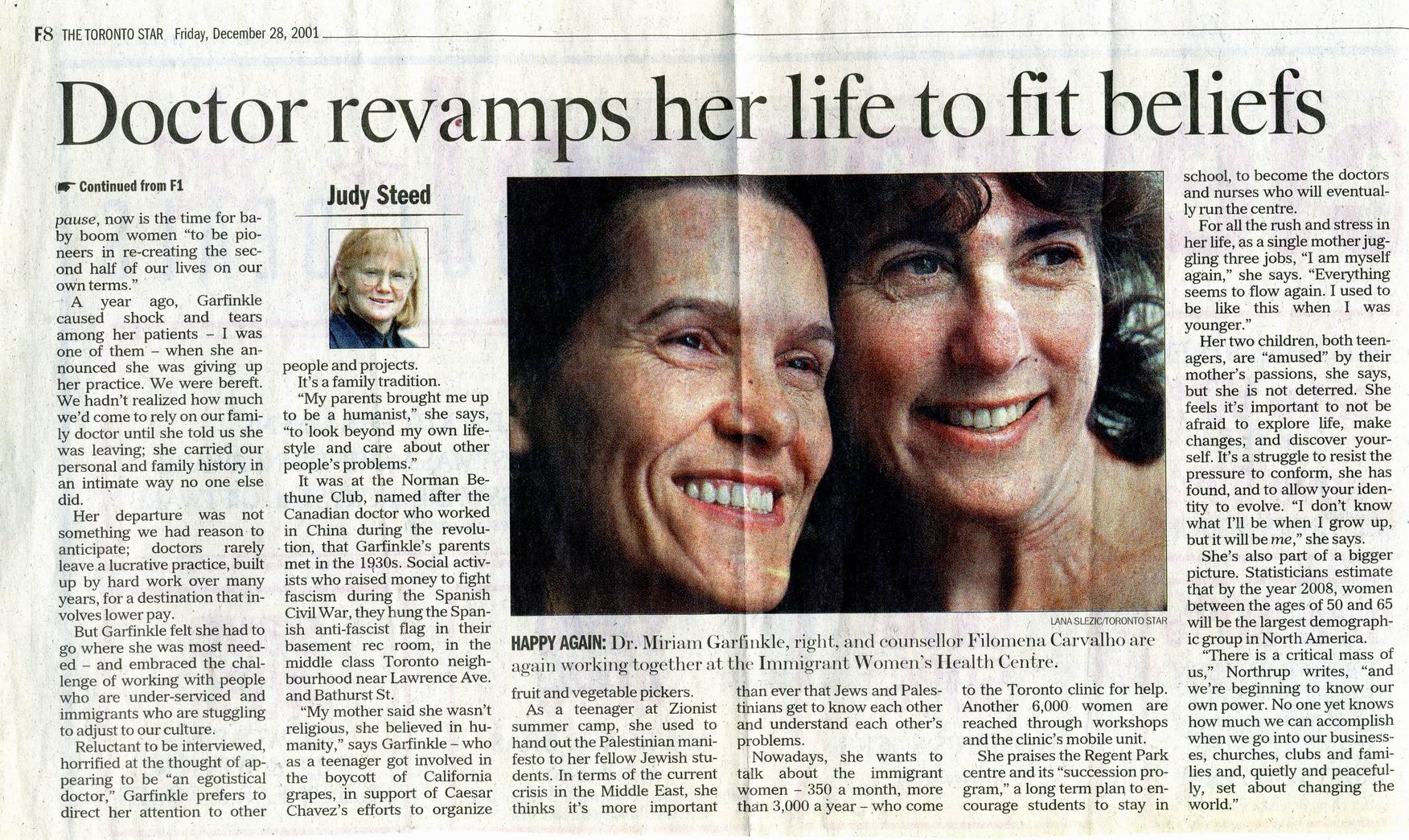

Making mid-life changesBy Judy Steed “I’m so much more myself.” So says Miriam Garfinkle, a family physician who recently left the busy Spadina Health Centre, which she established with her former husband in 1984, to work in community health. Last year, having ended her marriage, she went back to the Immigrant Women’s Health Centre, where she was the first woman doctor two decades ago, working with Filomena Carvalho, “who’s kept the centre alive all these years”, Garfinkle says. Leaving behind a private practice involving mostly middle class patients, to dedicate herself to Chinese, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Vietnamese and West Indian women, was an imperative Garfinkle couldn’t ignore. “I’m happier working on projects and things I believe in”, she says. And how. She recently joined the Regent Park Community Health Centre, where she works three days a week (in addition to one to two days a week with immigrant woman. She also fits in time at Hassle Free clinic on Church Street, dealing with young people.) It’s not every doctor’s idea of fun, but for Garfinkle, the dramatic changes in her life are framed by the fate of her mother, who died young, of breast cancer, when Garfinkle was only 20 years old. At 47, she realized life is short. “If there are things you want to do, you’d better do them while you can.” And when she moved out of the matrimonial home into her new apartment, the first piece of furniture she bought was a piano, to bring music to her life. Garfinkle is not alone in undergoing a mid-life transformation; it’s a process that’s affecting more and more women as their children grow up and they have time to reflect on personal needs. As Dr. Christiane Northrup puts it in her best-selling book, The Wisdom Of Menopause, now is the time for baby boom women “to be pioneers in re-creating the second half of their lives on our own terms.” A year ago Garfinkle caused shock and tears among her patients – I was one of them – when she announced she was giving up her practice. We were bereft. We hadn’t realized how much we’d come to rely on our family doctor until she told us she was leaving; she carried our personal and family history in an intimate way no one else did. Her departure was not something we had reason to anticipate; doctors rarely leave a lucrative practice, build up by hard work over many years, for a destination that involves lower pay. But Garfinkle felt she had to go where she was most needed – and embraced the challenge of working with people who are under-serviced and immigrants who are struggling to adjust to our culture. Reluctant to be interviewed, horrified at the thought of appearing to be “an egotistical doctor,” Garfinkle prefers to direct her attention to other people and projects. It’s a family tradition. “My parents brought me up to be a humanist,” she says, “to look beyond my own life-style and care about other people’s problems.” It was at the Norman Bethune Club, named after Canadian doctor who worked in China during the revolution, that Garfinkle’s parents met in the 1930s. Social activists who raised money to fight fascism during the Spanish Civil War, they hung the Spanish anti-fascist flag in the basement rec room, in the middle class Toronto neighbourhood near Lawrence Avenue and Bathurst Street. “My mother said she wasn’t religious, she believed in humanity,” says Garfinkle, who as a teenager got involved in the boycott of California grapes, in support of Caesar Chavez’s efforts to organize fruit and vegetable pickers. As a teenager at Zionist summer camp, she used to hand out the Palestinian manifesto to her fellow Jewish students. In terms of the current crisis in the Middle East, she thinks it’s more important than ever that Jews and Palestinians get to know each other’s problems. Nowadays, she wants to talk about the immigrant women – 350 a month, more than 3,000 a year – who come to the Toronto clinic for help. Another 6,000 women are reached through workshops and clinic mobile unit. She praises the Regent Park centre and its “succession program,” a long term plan to encourage students to stay in school, to become the doctors and nurses who will eventually run the centre. For all the rush and stress in her life, as a single mother juggling three jobs. “I am myself again,” she says. “Everything seems to flow again. I used to be like this when I was younger.” Her two children, both teenagers, are “amused” by their mother’s passions, she says, but she is not deterred. She feels it’s important to not be afraid to explore life, make changes, and discover yourself. It’s a struggle to resist the pressure to conform, she has found, and to allow your identity to evolve. “I don't know what I’ll be when I grow up, but it will be me,” she says. She’s also part of a bigger picture. Statisticians estimate that by the year 2008, women between the ages of 50 and 65 will be the largest demographic group in North America. “There is a critical mass of us,” Northrup writes, “and we’re beginning to know our own power. No one yet knows how much we can accomplish when we go into our businesses, churches, clubs and families and, quietly and peacefully, set about changing the world.”  This article is also available in Chinese and Spanish. |