Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

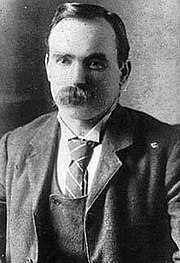

James Connolly

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| James Connolly | |

|---|---|

| 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916 (aged 47) | |

|

|

| Place of birth | Cowgate, Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Place of death | Kilmainham Jail, Dublin, Ireland |

| Allegiance | Irish Socialist Republican Party Irish Republican Brotherhood Irish Citizen Army Socialist Party of Ireland (1910) |

| Years of service | 1913–1916 |

| Rank | Commandant General |

| Battles/wars | Dublin Lockout Easter Rising |

James Connolly (5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish socialist leader. He was born in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, to Irish immigrant parents. He left school for working life at the age of 11, but became one of the leading Marxist theorists of his day. Though proud of his Irish background, he also took a role in Scottish and American politics. He was executed by a British firing squad because of his leadership role in the Easter Rising of 1916.

Contents |

James Connolly was born on 5 June 1868, at 107 Cowgate, Edinburgh. His parents, John and Mary Connolly, had emigrated to Edinburgh from County Monaghan in the 1850s. His father worked as a manure carter, removing dung from the streets at night, and his mother was a domestic servant who suffered from chronic bronchitis and died young from that ailment.

Anti-Irish feeling at the time was so prevalent[1] that Irish people were forced to live in the slums of the Cowgate and the Grassmarket which became known as 'Little Ireland'. Overcrowding, poverty, disease, drunkenness and unemployment were rife–the only jobs available were selling second-hand clothes and working as a porter or a carter. Later in life he listed his place of birth as "County Monaghan" in the 1901 and 1911 censuses.[2][3]

James Connolly went to St Patrick's School in the Cowgate, as did his two older brothers, Thomas and John. At ten years of age, James left school and got a job with the Edinburgh Evening News, where he worked as a 'Devil', cleaning inky rollers and fetching beer and food for the adult workers. His brother Thomas also worked with the same newspaper. In 1882, aged 14, he joined the British Army in which he remained for nearly seven years, mainly in Ireland (although also in India)[4].

While serving in Ireland, he met his future wife, a Protestant named Lillie Reynolds. They were engaged in 1888 and the following year Connolly discharged himself from the British Army and went back to Scotland.

In 1889 while living in Dundee James first got involved in socialist politics joining the Socialist League while his older brother John was involved in a free speech campaign alongside the Social Democratic Federation and the local Trades Council.

In 1890, James Connolly and Lillie Reynolds married in Perth. In the spring of that year, they moved to Edinburgh and lived at 22 West Port. The children of James and Lillie Connolly included Roddy and Nora, as well as Ina May, M¡ire and Fiona. James joined his father and brother working as a labourer and then as a manure carter with Edinburgh Corporation, on a strictly temporary and casual basis.

He became active in socialist and trade union circles and became secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation, almost by mistake. At the time his brother John was secretary; however, after John spoke at a rally in favour of the eight-hour day he was fired from his job with the corporation, so while he looked for work, James took over as secretary. During this time, Connolly became involved with the Independent Labour Party which Keir Hardie formed in 1893.

Sometime during this period, he took up the study of, and advocated the use of, the neutral international language, Esperanto.[5]

By 1892 he was involved in the Scottish Socialist Federation, acting as its secretary from 1895, but by 1896 he had gone to Dublin to take up the full time job of secretary of the Dublin Socialist Society, which at his instigation quickly evolved into the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP). The ISRP is regarded by many Irish historians as a party of pivotal importance in the early history of Irish socialism and republicanism. While active as a socialist in Great Britain Connolly was the founding editor of The Socialist newspaper and was among the founders of the Socialist Labour Party which split from the Social Democratic Federation in 1903. While in America he was member of the Socialist Labor Party of America (1906), the Socialist Party of America (1909) and the Industrial Workers of the World, and founded the Irish Socialist Federation in New York, 1907. On his return to Ireland he was right hand man to James Larkin in the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. He stood twice for the Wood Quay ward of Dublin Corporation but was unsuccessful. His name, and those of his family, appears in the 1911 Census of Ireland - his occupation listed as National Organiser Socialed Service[6]. In 1913, in response to the Lockout, he, along with an ex-British officer, Jack White, founded the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), an armed and well-trained body of labour men whose aim was to defend workers and strikers, particularly from the frequent brutality of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Though they only numbered about 250 at most, their goal soon became the establishment of an independent and socialist Irish nation. He founded the Irish Labour Party in 1912 and was a member of the National Executive of the Irish Labour Party. Around this time he met Winifred Carney in Belfast, who would become his secretary and accompany him during the Easter Rising.

Connolly stood aloof from the leadership of the Irish Volunteers. He considered them too bourgeois and unconcerned with Ireland's economic independence. In 1916, thinking they were merely posturing and unwilling to take decisive action against Britain, he attempted to goad them into action by threatening to send the ICA against the British Empire alone, if necessary. This alarmed the members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who had already infiltrated the Volunteers and had plans for an insurrection that very year. In order to talk Connolly out of any such rash action, the IRB leaders, including Tom Clarke and Patrick Pearse, met with Connolly to see if an agreement could be reached. It has been said [7] that he was kidnapped by them, but this has been denied of late[citation needed], and must at some point come down to a matter of semantics. As it was, he disappeared for three days without telling anyone where he had been. During the meeting the IRB and the ICA agreed to act together at Easter of that year.

When the Easter Rising occurred on 24 April 1916, Connolly was Commandant of the Dublin Brigade, and as the Dublin Brigade had the most substantial role in the rising, he was de facto Commander in Chief. Following the surrender, he said to other prisoners: "Don't worry. Those of us that signed the proclamation will be shot. But the rest of you will be set free." Connolly was not actually held in jail, but in a room (now called the "Connolly Room") at the State Apartments in Dublin Castle, which had been converted to a First Aid station for British Troops recovering from the war.[8] He was taken to Royal Hospital Kilmainham, across the road from the jail and then taken to the jail to be executed by the British. Visited by his wife, and asking about public opinion, he commented 'They all forget that I am an Irishman'. He confessed his sins, said to be his first religious act since marriage.

He was so badly injured from the fighting (a doctor had already said he had no more than a day or two to live, but the execution order was still given) that he was unable to stand before the firing squad. His absolution and last rites were administered by a Capuchin, Father Aloysius. Asked to pray for the soldiers about to shoot him, he said: "I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights".

Instead of being marched to the same spot where the others had been executed, at the far end of the execution yard, he was tied to a chair and then shot. The executions were not well received, even throughout Britain, and were drawing unwanted attention from the United States, which the British Government was trying to lure into the war in Europe. Herbert Asquith, the British Prime Minister, ordered that no more executions were to take place; an exception being that of Roger Casement as he had not yet been tried.

James Connolly was survived by his wife Lillie and several children, of whom Nora became an influential writer and campaigner within the Republican movement as an adult, and Roddy continued his father's politics. In later years both became members of the Oireachtas (Irish parliament).

Connolly was sentenced to death by firing squad for his part in the rising. On 12 May 1916 he was transported by military ambulance to Kilmainham Gaol, carried to a prison courtyard on a stretcher, tied to a chair and shot. His body (along with those of the other rebels) was put in a mass grave without a coffin. The executions of the rebels deeply angered the majority of the Irish population, most of whom had shown no support during the rebellion. It was Connolly's execution, however, that caused the most controversy. Historians have pointed to the actions of Connolly and similar rebels, as well as the manner of their execution as being factors that caused public awareness of their desires and goals, as well as gathering support for the movements that they had died fighting for.

His legacy in Ireland is mainly due to his contribution to the republican cause and his Marxism has been largely overlooked by mainstream histories (although his legacy as a socialist has been claimed by the Communist Party of Ireland, Connolly Youth Movement, irg, the IRSP, the Labour Party, Sinn Fin, the Socialist Party, the Socialist Workers Party, the Workers' Party, the Scottish Socialist Party and a variety of other left-wing and left-republican groups). However, despite claims to the contrary, Connolly's writings show him to be first and foremost a Marxist thinker.[citation needed] In several of his works he rails against the bourgeois nationalism of those who claimed to be Irish patriots. Connolly was among the few European members of the Second International who opposed, outright, World War I. This put him at odds with most of the Socialist leaders of Europe. He was influenced by and heavily involved with the radical Industrial Workers of the World labour union.

Apparently, Lenin was a great admirer of Connolly,[citation needed] although the two never met. Lenin berated other communists, who had criticised the rebellion in Ireland as bourgeois. He maintained that no revolution was "pure", and communists would have to unite with other disaffected groups in order to overthrow existing social orders. He was to prove his point the next year, during the Russian Revolution.

In Scotland, Connolly's thinking was hugely influential to socialists such as John Maclean, who would similarly combine his leftist thinking with nationalist ideas when he formed his Scottish Workers Republican Party.

There is a statue of James Connolly in Dublin, outside Liberty Hall, the offices of the SIPTU Trade Union.

In a 1972 interview on the Dick Cavett Show, John Lennon stated that James Connolly was an inspiration for his song, Woman Is the Nigger of the World. Lennon quoted Connolly's 'the female is the slave of the slave' in explaining the pro-feminist inspiration behind the song.[9]

Connolly Station, one of the two main railway stations in Dublin, and Connolly Hospital, Blanchardstown, are named in his honour.

In a 2002 BBC television production, 100 Greatest Britons where the British public were asked to register their vote, Connolly was voted in 64th place.

| This page is a candidate to be copied to Wikiquote using the Transwiki process. If the page can be expanded into an encyclopedic article, rather than a list of quotes, please do so and remove this message. |

James Connolly's personal religious convictions are a matter of conjecture. He declared himself a Roman Catholic in the Dublin Census of 1911.[10] In the only written record made by Connolly about his personal position in relation to Catholicism, he stated:

though I have usually posed as a Catholic, I have not done my duty for 15 years, and have not the slightest tincture of faith left–

– (Letter from James Connolly to John Carstairs Matheson, 30 January 1908)[11]

Labour, Nationality and Religion:

| – | The day has passed for patching up the capitalist system; it must go. And in the work of abolishing it the Catholic and the Protestant, the Catholic and the Jew, the Catholic and the Freethinker, the Catholic and the Buddhist, the Catholic and the Mahometan will co-operate together, knowing no rivalry but the rivalry of endeavour toward an end beneficial to all. For, as we have said elsewhere, socialism is neither Protestant nor Catholic, Christian nor Freethinker, Buddhist, Mahometan, nor Jew; it is only Human. We of the socialist working class realise that as we suffer together we must work together that we may enjoy together. We reject the firebrand of capitalist warfare and offer you the olive leaf of brotherhood and justice to and for all. | – |

An earlier work also published by the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP), called Socialism and Religion, where Connolly says of socialism:

| – | We do not mean that its supporters are necessarily materialists in the vulgar, and merely anti-theological, sense of the term, but that they do not base their socialism upon any interpretation of the language or meaning of scripture, nor upon the real or supposed intentions of a beneficent Deity. They as a party neither affirm or deny those things, but leave it to the individual conscience of each member to determine what beliefs on such questions they shall hold. As a political party they wisely prefer to take their stand upon the actual phenomena of social life as they can be observed in operation amongst us to-day, or as they can be traced in the recorded facts of history | – |

Scott Herbert, however, called him a "devout Catholic".[12] Father Aloysius in conversation to his daughter Nora:

| – | It was a terrible shock to me, I'd been with him that evening and I promised to come to him this afternoon. I felt sure there would be no more executions. Your father was much easier than he had been. I was sure that he would get his first real night's rest. The ambulance that brought you home came for me. I was astonished. I had felt so sure that I would not be needed. For the first time since the Rising, I had locked the doors. And some time after two I was knocked up. The ambulance brought me to your father. Such a wonderful man - such a concentration of mind. They carried him from his bed in an ambulance stretcher down to a waiting ambulance and drove him to Kilmainham Jail. They carried him from the ambulance to the jail yard and put him in a chair. He was very brave and cool. I said to him, "Will you pray for the men who are about to shoot you" and he said: "I will say a prayer for all brave men who do their duty." His prayer was "Forgive them for they know not what they do" and then they shot him.[13] | – |

Selected extracts from the personal recollections of Father Aloysius OFM Cap.[14]

| – | Monday 1 May

Early in the morning the son of Superintendent Dunne (DMP) a subdeacon, called to me and said that Father Murphy, the military chaplain, had sent him to ask if I could call to the Castle during the afternoon. James Connolly, who was a prisoner and a patient there, had expressed a wish to see me. I called, and saw Father Murphy. He told me that he had arranged for the necessary permissions. With Captain Stanley, RAMC, I went to the ward. At the door the sentry challenged Captain Stanley and informed him he had orders to allow no one to see the prisoner without special instructions. Captain Stanley was obliged to return for his permit. The sentry asked me if I were Father Aloysius and, on my replying in the affirmative said: 'You can go in.' However, as the nurses were engaged with Connolly, I delayed outside until they had finished and Captain Stanley had returned. I entered with Captain Stanley, but I remarked that two soldiers with rifles and bayonets were on guard and showed no intention of leaving. I point out this to Captain Stanley, but he said it was necessary that they should remain; that he had no power to remove them. Then I said: 'If that is so I cannot do my work as a priest. I have never before, to my knowledge spoken to James Connolly. I cannot say if he may not be hard of hearing. Confession is an important and sacred duty that demands privacy and I cannot go on with it in the presence of these men.' I had given my word that I would not utilise the opportunity for carrying political information or as a cover for political designs, and if my word was not sufficient or reliable they had better get some other priest. But I felt quite confident I would have my way. |

– |

| – | Tuesday 2nd

In the morning I gave Holy Communion to James Connolly. Later in the day I went with Father Augustine to Headquarters, Infirmary Road and met General (Sir John) Maxwell.... When I reached Kilmainham Gaol I was informed that Thomas MacDonagh also wished for my ministrations. I was taken to the prisoners' cells and spent some hours between the two. "You will be glad to know that I gave Holy Communion to James Connolly this morning," I said to Pearse when I met him. "Thank God," he replied, "it is the one thing I was anxious about." |

– |

| – | Thursday afternoon

Called to the Castle to see Connolly. Connolly had not slept and seemed feverish. I said that I would let him rest and would called in morning to give him Holy Communion. Uneasy about him I tried to get contact with Captain Stanley, but he could not be found. Reached Castle gates, and, still uneasy, decided to return and make another attempt to see Stanley. Saw him and was assured that there was no danger of any steps being taken; he reminded me that Asquith had given to understand that no executions would take place pending debate which was on that night. Got back to Church Street some time near 7 pm. About 9 pm Captain Stanley called and told me that my services would be required about 2 am. He was not at liberty to say more but I could understand. |

– |

| – | Friday Morning, 12th

About 1 am car called and Father Sebastian accompanied me to Castle. Heard Connolly's confession and gave him Holy Communion. Waited in Castle Yard while he was being given a meal. He was brought down and laid on stretcher in ambulance. Father Sebastian and myself drove with him to Kilmainham. Stood behind firing party during the execution. Father Eugene McCarthy, who had attended Sean MacDermott before we arrived, remained and anointed Connolly immediately after the shooting. |

– |

Three months after James Connolly's execution his wife Lillie (ne Lillie Reynolds, a domestic servant from Co Wicklow) was received into the Catholic Church, at Church St. on 15 August.[15].

Whilst in the United States where he had joined the Socialist Labour Party in 1903, he clashed with party leader Daniel De Leon, who called Connolly, amongst other things, a "Jesuit spy."[16]

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: James Connolly |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

|

||||||||||||||

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions