Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

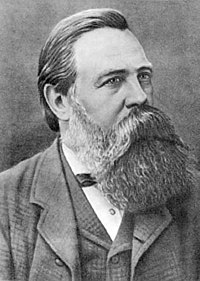

Friedrich Engels

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Friedrich Engels |

|

| Full name | Friedrich Engels |

|---|---|

| Born | 28 November 1820 Barmen, Prussia |

| Died | 5 August 1895 (aged 74) London, England |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Marxism |

| Main interests | Political philosophy, Politics, Economics, class struggle, capitalism |

| Notable ideas | Co-founder of Marxism (with Karl Marx), alienation and exploitation of the worker, historical materialism |

| Signature |  |

Friedrich Engels (German pronunciation: [ÉÅÉls]; 28 November 1820 – 5 August 1895) was a German social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of communist theory, alongside Karl Marx. Together they produced The Communist Manifesto in 1848. Engels also edited the second and third volumes of Das Kapital after Marx's death.

Contents |

Friedrich Engels was born in Barmen, Rhine Province of the kingdom of Prussia (now part of Wuppertal in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) as the elder son of a German textile manufacturer, with whom he had a strained relationship.[1] Due to family circumstances, Engels dropped out of high school and was sent to work as a nonsalaried office clerk at a commercial house in Bremen in 1838.[2][3]

During this time, Engels began reading the philosophy of Hegel, whose teachings had dominated German philosophy at the time. In September 1838, he published his first work, a poem titled The Bedouin, in the Bremisches Conversationsblatt No. 40. He also engaged in other literary and journalistic work.[4][5]

In 1841, Engels joined the Prussian Army as a member of the Household Artillery. This position moved him to Berlin where he attended university lectures, began to associate with groups of Young Hegelians and published several articles in the Rheinische Zeitung.[3] Throughout his lifetime, Engels would point out that he was indebted to German philosophy because of its effect on his intellectual development.[2]

In 1842, the 22-year-old Engels was sent to Manchester, Britain to work for the textile firm of Ermen and Engels in which his father was a shareholder.[6][7] Engels' father thought that working at the Manchester firm might make Engels reconsider the radical leanings that he had developed in high school.[2][7] On his way to Manchester, Engels visited the office of the Rheinische Zeitung and met Karl Marx for the first time - though they did not impress each other.[8]

In Manchester, Engels met Mary Burns, a young woman with whom he began a relationship that lasted until her death in 1862.[9] Mary acted as a guide through Manchester and helped introduce Engels to the English working class. The two maintained a lifelong relationship; they never married, as Engels was against the institution of marriage, which he saw as unnatural and unjust.[10]

During his time in Manchester, Engels took notes of the horrors he observed there, notably child labor, the despoiled environment, and overworked and impoverished laborers.[11] These notes and observations, along with his experience working in his father's commercial firm, formed the basis for his views on the "grim future of capitalism and the industrial age", outlined in his first book The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844.[11]

While writing it, Engels continued his involvement with radical journalism and politics. He frequented some areas also frequented by some members of the English labour and Chartist movements, whom he met, and wrote for several journals, including The Northern Star, Robert Owen–s New Moral World and the Democratic Review newspaper.[9][12][13]

After a productive stay in Britain, Engels decided to return to Germany in 1844. On his way, he stopped in Paris to meet Karl Marx, with whom he had an earlier correspondence. Marx and Engels met at the Caf de la Rgence on the Place du Palais, 28 August 1844. The two became close friends and would remain so for their entire lives.

Engels ended up staying in Paris to help Marx write The Holy Family, which was an attack on the Young Hegelians and the Bauer brothers. Engels' earliest contribution to Marx's work was writing to the Deutsch-franzsische Jahrbcher journal, which was edited by both Marx and Arnold Ruge in Paris in the same year.[6]

From 1845 to 1848, Engels and Marx lived in Brussels, spending much of their time organizing the city's German workers. Shortly after their arrival, they contacted and joined the underground German Communist League and were commissioned by the League to write a pamphlet explaining the principles of communism. This became The Manifesto of the Communist Party, better known as the Communist Manifesto. It was first published on 21 February 1848.[2]

During February 1848, there was a revolution in France that eventually spread to other Western European countries. This event caused Engels & Marx to go back to their home country of Prussia, specifically the city of Cologne. While living in Cologne, they created and served as editors for a new daily newspaper called the Neue Rheinische Zeitung.[6]

However, during the June 1849 Prussian coup d'tat the newspaper was suppressed. After the coup, Marx lost his Prussian citizenship, was deported, and fled to Paris and then London. Engels stayed in Prussia and took part in an armed uprising in South Germany as an aide-de-camp in the volunteer corps of August Willich.[14] When the uprising was crushed, Engels managed to escape by traveling through Switzerland as a refugee and returned to England.[2]

Once Engels made it to Britain, he decided to re-enter the commercial firm where his father held shares in order to help support Marx. He hated this work intensely but knew that his friend needed the support.[15][16] He started off as an office clerk, the same position he held in his teens, but eventually worked his way up to become a partner in 1864. Five years later, Engels retired from the business to focus more on his studies.[6]

At this time, Marx was living in London but they were able to exchange ideas through daily correspondence. In 1870, Engels moved to London where he and Marx lived until Marx's death in 1883.[2] His London home at this time and until his death was 122 Regent's Park Road, Primrose Hill, NW1.[17] Marx's first London residence was a cramped apartment at 28 Dean Street, Soho. From 1856, he lived at 9 Grafton Terrace, Kentish Town, and then in a tenement at 41 Maitland Park Road from 1875 until his death.[18]

After Marx's death, Engels devoted much of his remaining years to editing Marx's unfinished volumes of Capital. However, he also contributed significantly to other areas. Engels made an argument using anthropological evidence of the time to show that family structures have changed over history, and that the concept of monogamous marriage came from the necessity within class society for men to control women to ensure their own children would inherit their property. He argued a future communist society would allow people to make decisions about their relationships free from economic constraints. One of the best examples of Engels' thoughts on these issues are in his work The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Engels died of throat cancer in London in 1895.[19] Following cremation at Brookwood Cemetery near Woking, his ashes were scattered off Beachy Head, near Eastbourne as he had requested.[19][20]

Engels is commonly known as a "ruthless party tactician", "brutal ideologue", and "master tactician" when it came to purging rivals in political organizations. However, another strand of Engels–s personality was one of a "gregarious", "bighearted", and "jovial man of outsize appetites", who was referred to by his son-in-law as "the great beheader of champagne bottles."[11] His interests included poetry, fox hunting, and he hosted regular Sunday parties for London–s left-wing intelligentsia where as one regular put it, "no one left before 2 or 3 in the morning." His stated personal motto was "take it easy", while "jollity" was listed as his favorite virtue.[11]

Tristram Hunt, author of Marx–s General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels, sums up the disconnect between Engel's personality, and those Soviets who later utilized his works, stating:

Tristram Hunt argues that Engels has become a convenient scapegoat, too easily blamed for the state crimes of the Soviet Union, Communist Southeast Asia and China. "Engels is left holding the bag of 20th century ideological extremism," Hunt writes, "while Marx is rebranded as the acceptable, postpolitical seer of global capitalism."[11] Hunt largely exonerates Engels stating that "in no intelligible sense can Engels or Marx bear culpability for the crimes of historical actors carried out generations later, even if the policies were offered up in their honor."[11]

Paul Thomas, of the University of California, Berkeley, claims that while Engels had been the most important and dedicated facilitator and diffuser of Marx's writings, he significantly altered Marx's intents as he held, edited and released in a finished form, and commentated on them. Engels attempted to fill gaps in Marx's system and to extend it to other fields. He stressed in particular Historical Materialism, assigning it a character of scientific discovery and a doctrine, indeed forming Marxism as such. A case in point is Anti-Dhring, which supporters of socialism like its detractors treated as an encompassing presentation of Marx's thought. And while in his extensive correspondence with German socialists Engels honestly presented his own secondary place in the couple's intellectual relationship, Russian communists who had no available direct evidence, raised Engels up with Marx and conflated their thoughts as if they were necessarily congruous. Soviet Marxists then developed this tendency to the state doctrine of Dialectical Materialism.[21]

The Holy Family was a book written by Marx & Engels in November 1844. The book is a critique on the Young Hegelians and their trend of thought which was very popular in academic circles at the time. The title was a suggestion by the publisher and is meant as a sarcastic reference to the Bauer Brothers and their supporters.[22]

The book created a controversy with much of the press and caused Bruno Bauer to attempt to refute the book in an article which was published in Wigand's Vierteljahrsschrift in 1845. Bauer claimed that Marx and Engels misunderstood what he was trying to say. Marx later replied to his response with his own article that was published in the journal Gesellschaftsspiegel in January 1846. Marx also discussed the argument in chapter 2 of The German Ideology.[22]

The Condition of the Working Class is a detailed description and analysis of the appalling conditions of the working class in Britain and Ireland during Engels' stay in England. It was considered a classic in its time and still widely available today. This work also had many seminal thoughts on the state of socialism and its development.

Popularly known as Anti-Dhring, Herr Eugen Dhring's Revolution in Science is a detailed critique of the philosophical positions of Eugen Dhring, a German philosopher and critic of Marxism. In the course of replying to Dhring, Engels reviews recent advances in science and mathematics and seeks to demonstrate the way in which the concepts of dialectics apply to natural phenomena. Many of these ideas were later developed in the unfinished work, Dialectics of Nature. The last section of Anti-Dhring was later edited and published under the separate title, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.

In what Engels presented as an extraordinarily popular piece,[23] Engels critiques the utopian socialists, such as Fourier and Owen, and provides an explanation of the socialist framework for understanding capitalism.

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State is an important and detailed seminal work connecting capitalism with what Engels argues is an ever changing institution - the family. It was written when Engels was 64 years of age and at the height of his intellectual power and contains a comprehensive historical view of the family in relation to the issues of class, female subjugation and private property.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Friedrich Engels |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Friedrich Engels |

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions