Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Susan B. Anthony

Susan Brownell Anthony (February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was a prominent American civil rights leader who played a pivotal role in the 19th century women's rights movement to introduce women's suffrage into the United States. She traveled the United States, and Europe, and gave 75 to 100 speeches every year on women's rights for 45 years.

[edit] Early lifeSusan B. Anthony was born and raised in West Grove, near Adams, Massachusetts. She was the second oldest of seven children–Guelma Penn (1818–1873), Hannah Lapham (1821–1877), Daniel Read (1824–1904), Mary Stafford (1827–1907), Eliza Tefft (1832–1834), and Jacob Merritt (1834–1900)–born to Daniel Anthony (1794–1862) and Lucy Read (1793–1880). One brother, publisher Daniel Read Anthony, would become active in the anti-slavery movement in Kansas, while a sister, Mary Stafford Anthony, became a teacher and a woman's rights activist. Anthony remained close to her sisters throughout her life. Anthony's father Daniel was a cotton manufacturer and abolitionist, a stern but open-minded man who was born into the Quaker religion.[1] He did not allow toys or amusements into the household, claiming that they would distract the soul from the "inner light." Her mother Lucy was a student in Daniel's school; the two fell in love and agreed to marry in 1817, but Lucy was less sure about marrying into the Society of Friends (Quakers). She attended the Rochester women–s rights convention held in August 1848, two weeks after the historic Seneca Falls Convention, and signed the Rochester convention–s Declaration of Sentiments. Lucy and Daniel Anthony enforced self-discipline, principled convictions, and belief in one's own self-worth. Susan was a precocious child, having learned to read and write at age three.[2] In 1826, when she was six years old, the Anthony family moved from Massachusetts to Battenville, New York. Susan was sent to attend a local district school, where a teacher refused to teach her long division because of her gender. Upon learning of the weak education she was receiving, her father promptly had her placed in a group home school, where he taught Susan himself. Mary Perkins, another teacher there, conveyed a progressive image of womanhood to Anthony, further fostering her growing belief in women's equality. In 1837, Anthony was sent to Deborah Moulson's Female Seminary, a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia. She was not happy at Moulson's, but she did not have to stay there long. She was forced to end her formal studies because her family, like many others, was financially ruined during the Panic of 1837. Their losses were so great that they attempted to sell everything in an auction, even their most personal belongings, which were saved at the last minute when Susan's uncle, Joshua Read, stepped up and bid for them in order to restore them to the family. In 1839, the family moved to Hardscrabble, New York, in the wake of the panic and economic depression that followed. That same year, Anthony left home to teach and to help pay off her father's debts. She taught first at Eunice Kenyon's Friends' Seminary, and then at the Canajoharie Academy in 1846, where she rose to become headmistress of the Female Department. Anthony's first occupation inspired her to fight for wages equivalent to those of male teachers, since men earned roughly four times more than women for the same duties. In 1849, at age 29, Anthony quit teaching and moved to the family farm in Rochester, New York. She began to take part in conventions and gatherings related to the temperance movement. In Rochester, she attended the local Unitarian Church and began to distance herself from the Quakers, in part because she had frequently witnessed instances of hypocritical behavior such as the use of alcohol amongst Quaker preachers. As she got older, Anthony continued to move further away from organized religion in general, and she was later chastised by various Christian religious groups for displaying irreligious tendencies. In her youth, Anthony was very self-conscious of her looks and speaking abilities. She long resisted public speaking for fear she would not be sufficiently eloquent. Despite these insecurities, she became a renowned public presence, eventually helping to lead the women's movement. [edit] Early social activismUniversal manhood suffrage, by establishing an aristocracy of sex, imposes upon the women of this nation a more absolute and cruel despotism than monarchy; in that, woman finds a political master in her father, husband, brother, son. The aristocracies of the old world are based upon birth, wealth, refinement, education, nobility, brave deeds of chivalry; in this nation, on sex alone; exalting brute force above moral power, vice above virtue, ignorance above education, and the son above the mother who bore him. National Woman Suffrage Association.[3]

In the era before the American Civil War, Anthony took a prominent role in the New York anti-slavery and temperance movements. In 1836, at age 16, Susan collected two boxes of petitions opposing slavery, in response to the gag rule prohibiting such petitions in the House of Representatives.[4] In 1849, at age 29, she became secretary for the Daughters of Temperance, which gave her a forum to speak out against alcohol abuse, and served as the beginning of Anthony's movement towards the public limelight. In late 1850, Anthony read a detailed account in the New York Tribune of the first National Women's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. In the article, Horace Greeley wrote an especially admiring description of the final speech, one given by Lucy Stone. Stone's words catalyzed Anthony to devote her life to women's rights.[5] In the summer of 1852, Anthony met both Greeley and Stone in Seneca Falls.[6] In 1851, on a street in Seneca Falls, Anthony was introduced to Elizabeth Cady Stanton by a mutual acquaintance, as well as fellow feminist Amelia Bloomer. Anthony joined with Stanton in organizing the first women's state temperance society in America after being refused admission to a previous convention on account of her sex, in 1851. Stanton remained a close friend and colleague of Anthony's for the remainder of their lives, but Stanton longed for a broader, more radical women's rights platform. Together, the two women traversed the United States giving speeches and attempting to persuade the government that society should treat men and women equally. Anthony was invited to speak at the third annual National Women's Rights Convention held in Syracuse, New York in September 1852. She and Matilda Joslyn Gage both made their first public speeches for women's rights at the convention.[7] Anthony began to gain notice as a powerful public advocate of women's rights and as a new and stirring voice for change. Anthony participated in every subsequent annual National Women's Rights Convention, and served as convention president in 1858. In 1856, Anthony further attempted to unify the African-American and women's rights movements when, recruited by abolitionist Abby Kelley Foster,[8] she became an agent for William Lloyd Garrison's American Anti-Slavery Society of New York. Speaking at the Ninth National Women–s Rights Convention on May 12, 1859, Anthony asked "Where, under our Declaration of Independence, does the Saxon man get his power to deprive all women and Negroes of their inalienable rights?" [edit] The RevolutionOn January 1, 1868, Anthony first published a weekly journal entitled The Revolution. Printed in New York City, its motto was: "The true republic–men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less." Anthony worked as the publisher and business manager, while Elizabeth Cady Stanton acted as editor. The main thrust of The Revolution was to promote women–s and African-Americans– right to suffrage, but it also discussed issues of equal pay for equal work, more liberal divorce laws and the church–s position on women–s issues. The journal was backed by independently wealthy George Francis Train, who provided $600 in starting funds. His financial support ceased by May 1869, and the paper began to operate in debt. Anthony insisted on expensive, high-quality printing equipment, and she paid women workers the high wages she thought they deserved. She banned any advertisements for alcohol- and morphine-laden patent medicines; all such medicines were abhorrent to her. However, revenue from non-patent-medicine advertisements was too low to cover costs.[9] In June 1870, Laura Curtis Bullard, a Brooklyn-based writer whose parents became wealthy from selling a popular morphine-containing patent medicine called "Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup", bought The Revolution for one dollar, with Anthony assuming its $10,000 debt, an amount equal to $171,000 in current value. Anthony used her lecture fees to repay the debt, completing the task in six years. Under Bullard, the journal adopted a literary orientation and accepted patent medicine ads, but it folded in February 1872.[10] [edit] American Equal Rights AssociationIn 1869, long-time friends Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony found themselves, for the first time, on opposing sides of a debate. The American Equal Rights Association (AERA), which had originally fought for both blacks– and women–s right to suffrage, voted to support the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, granting suffrage to black men, but not women. Anthony questioned why women should support this amendment when black men were not continuing to show support for women–s voting rights. Partially as a result of the decision by the AERA, Anthony soon thereafter devoted herself almost exclusively to the agitation for women's rights. On November 18, 1872, Anthony was arrested by a U.S. Deputy Marshal for voting illegally in the 1872 Presidential Election two weeks earlier. She had written to Stanton on the night of the election that she had "positively voted the Republican ticket–straight...". She was tried and convicted seven months later, despite the stirring and eloquent presentation of her arguments that the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed to "all persons born or naturalized in the United States" the privileges of citizenship, and which contained no gender qualification, gave women the constitutional right to vote in federal elections. Her trial took place at the Ontario County courthouse in Canandaigua, New York. The sentence was a fine, but not imprisonment; and true to her word in court, she never paid the penalty for the rest of her life. The trial gave Anthony the opportunity to spread her arguments to a wider audience than ever before.[11] Anthony toured Europe in 1883 and visited many charitable organizations. She wrote of a poor mother she saw in Killarney that had "six ragged, dirty children" to say that "the evidences were that 'God' was about to add a No. 7 to her flock. What a dreadful creature their God must be to keep sending hungry mouths while he withholds the bread to fill them!"[12] In 1893, she joined with Helen Barrett Montgomery in forming a chapter of the Woman–s Educational and Industrial Union (WEIU)[13] in Rochester. In 1898, she also worked with Montgomery to raise funds to open opportunities for women students to study at University of Rochester. [edit] National suffrage organizationsIn 1869, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton founded the National Woman's Suffrage Association (NWSA), an organization dedicated to gaining women's suffrage. Anthony was vice-president-at-large of the NWSA from the date of its organization until 1892, when she became president.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (sitting) with Anthony

In the early years of the NWSA, Anthony made many attempts to unite women in the labor movement with the suffragist cause, but with little success. She and Stanton were delegates at the 1868 convention of the National Labor Union. However, Anthony inadvertently alienated the labor movement not only because suffrage was seen as a concern for middle-class rather than working-class women, but because she openly encouraged women to achieve economic independence by entering the printing trades, where male workers were on strike at the time. Anthony was later expelled from the National Labor Union over this controversy. In 1890, Anthony orchestrated the merger of the NWSA with the more moderate American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), creating the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Prior to the controversial merge, Anthony had created a special NWSA executive committee to vote on whether they should merge with the AWSA, despite the fact that using a committee instead of an all-member vote went against the NWSA constitution. Motions to make it possible for members to vote by mail were strenuously opposed by Anthony and her adherents, and the committee was stacked with members who favored the merger. (Two members who voted against the merger were asked to resign). Anthony's pursuit of alliances with moderate suffragists created long-lasting tension between herself and more radical suffragists like Stanton. Stanton openly criticized Anthony's stance, writing that Anthony and AWSA leader Lucy Stone "see suffrage only. They do not see woman's religious and social bondage."[14] Anthony responded to Stanton: "We number over ten thousand women and each one has opinions ... and we can only hold them together to work for the ballot by letting alone their whims and prejudices on other subjects!"[15] The creation of the NAWSA effectively marginalized the more radical elements within the women's movement, including Stanton. Anthony pushed for Stanton to be voted in as the first NAWSA president, and stood by her as Stanton was belittled by the large factions of less-radical members within the new organization. In collaboration with Stanton, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Ida Husted Harper, Anthony published The History of Woman Suffrage (4 vols., New York, 1884–1887). Anthony also befriended Josephine Brawley Hughes, an advocate of women's rights and Prohibition in Arizona, and Carrie Chapman Catt, whom Anthony endorsed for the presidency of the NAWSA when Anthony formally retired in 1900. [edit] Later personal life, deathAfter retiring in 1900, Anthony remained in Rochester, where she died of heart disease and pneumonia in her house at 17 Madison Street on March 13, 1906.[16] She was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery. Following her death, the New York State Senate passed a resolution remembering her "unceasing labor, undaunted courage and unselfish devotion to many philanthropic purposes and to the cause of equal political rights for women."[17] [edit] LegacySusan B. Anthony, who died 14 years before passage of the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote, was honored as the first real (non-allegorical) American woman on circulating U.S. coinage with her appearance on the Susan B. Anthony dollar. The coin, approximately the size of a U.S. quarter, was minted for only four years, 1979, 1980, 1981, and 1999. Anthony dollars were minted for circulation at the Philadelphia and Denver mints for all four years, and at the San Francisco mint for the first three production years. She was featured on a 3– U.S. commemorative stamp in 1936 and a 50– Liberty Issue regular issue stamp on August 25, 1955. Anthony's birthplace in Adams was purchased in August 2006 by Carol Crossed, founder of the New York chapter of Democrats for Life of America, affiliated with Feminists for Life.[18] Anthony's childhood home in Battenville, New York, was placed on the New York State Historic Register in 2006, and the National Historic Register in 2007.[19]

Susan B. Anthony House in 1967

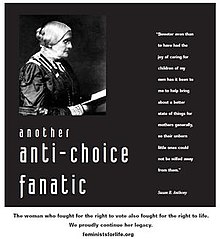

The Susan B. Anthony House in Rochester was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1966 and was operated as a museum.[20] The American composer Virgil Thomson and poet Gertrude Stein wrote an opera, The Mother of Us All, that abstractly explores Anthony's life and mission. Along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, she is commemorated in The Woman Movement, a sculpture by Adelaide Johnson, unveiled in 1921 at the United States Capitol. [edit] Dispute over abortionBeginning in 1989,[21] a dispute arose regarding Anthony's position on abortion, and the debate continues today. Pro-life activists use Anthony's image and words to promote their cause, but academic history experts[21] who have reviewed her private letters and published texts say that she mostly worked to win women the vote, that she was reticent to discuss sexual topics, and that her thoughts on abortion laws were never expressed.[22] Some of these academic scholars believe that the words used by pro-life organizations have been taken out of context or incorrectly attributed.[22][23] However, the pro-life groups have had an effect: because of the recasting of her as vital to the topic, American students today "routinely assume Anthony opposed abortion".[23]

Anthony image and quoted text, used by Feminists for Life to portray her as "anti-choice"

The organization Susan B. Anthony List, which supports pro-life politicians, writes that Anthony was "an outspoken critic of abortion",[24] and a similar group, Feminists for Life (FFL), makes extensive use of her words and images in their work.[22] A letter that Anthony wrote to Frances Willard in 1889 has been presented by both the SBA List and FFL to indicate her stance on abortion: "Sweeter even than to have had the joy of caring for children of my own has it been to me to help bring about a better state of things for mothers generally, so that their unborn little ones could not be willed away from them."[25][26][27] SBA List President Marjorie Dannenfelser adds that these words "speak for themselves".[26] However, in 1998, Mary Krane Derr, FFL's foremost historian, determined the context of Anthony's words to be unrelated to abortion; instead, she was referring to her victory in overturning a law which extended past death a father's absolute control of his children, through the means of his last will, resulting in a baby's fate determined by the father's legal estate if it was born after his death; the newborn could be "willed away" from its mother.[27] Derr says that Anthony's "comments relating to abortion are few", but describes "Social Purity", an anti-alcohol, anti-prostitution and pro-suffrage speech given repeatedly by Anthony in the 1870s, as one that is "more explicit".[28] After naming alcohol abuse as a major social evil and estimating that there are 600,000 American men who are drunkards, Anthony describes in her speech how liquor traffic extends "deep and wide into the financial structure of the government" and that it must be fought with "one earnest, energetic, persistent force."[29] She continues:

Historian and journalist Marvin Olasky writes that the social purity movement began in the late 1860s with British feminist Josephine Butler working to improve the welfare of prostitutes; the American feminist version of the movement intended to abolish prostitution, and Anthony sided with this cause in 1872.[30] Estelle B. Freedman, Professor of History and a founder of the Program in Feminist Studies at Stanford University, writes that Anthony's "Social Purity" speech "linked drunkenness to the sexual abuse of women" and that women's occupational and wage discrimination, leading desperately poor women to prostitution, was described by her as depending "on the denial of equal suffrage".[31] Of primary importance to Anthony was the granting to woman the right to control her own body.[21] She saw this as an essential element for the prevention of unwanted pregnancies, using abstinence as the method. Pro-life activists claim that Anthony wrote a letter published in The Revolution in 1869 called "Marriage and Maternity"; in it the writer discusses the subject of abortion, arguing that instead of merely attempting to pass a law against abortion, the root cause must also be addressed: man's unthinking gratification of his sexual urges upon woman.[32] The writer remonstrates against abortion, saying "guilty? Yes, no matter what the motive, love of ease, or a desire to save from suffering the unborn innocent, the woman is awfully guilty who commits the deed. It will burden her conscience in life, it will burden her soul in death; but oh! thrice guilty is he who, for selfish gratification, heedless of her prayers, indifferent to her fate, drove her to the desperation which impelled her to the crime."[32] Anthony researchers and authors Ann D. Gordon and Lynn Sherr dispute Anthony's authorship, writing, "the bits of information circulating on the Web always cite 'Marriage and Maternity', an article in a newspaper owned ... by Susan B. Anthony. In it, the writer ... signs it simply, 'A'. Although no data exist that Anthony wrote it, or ever used that shorthand for herself, she is imagined to be its author."[33] Derr concedes that she could be wrong about the article's authorship, but says that Anthony, as the publisher of the journal, "most likely agreed with the author's position".[21] Gordon, referring to the article's many scriptural quotes and appeals to God, notes that its style does not fit with Anthony's "known beliefs".[23] Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and columnist Stacy Schiff points out that the proponents of Anthony as an abortion rights foe generally fail to mention that the letter writer "argues against an anti-abortion law ... [the] author did not believe legislation would resolve the issue of unwanted pregnancy."[18] Allison Stevens, the Washington bureau chief at Women's eNews, wrote that pro-choice activists are outraged that the memory of Anthony "is being appropriated by a community led by the very people Anthony battled during her lifetime: social conservatives."[23] Nora Bredes, the director of the Susan B. Anthony Center for Women's Leadership at the University of Rochester in New York and a Democratic politician who supports abortion rights,[34] said in 2006 that she wished to "reclaim Anthony's legacy".[23] Anthony's journal, The Revolution, never advocated abortion or birth control, but certainly pushed for woman's right to control her own body "as an autonomous and self-directing human being".[35] Gordon stated in February 2010, "we can't say what her stance on abortion would be, but we can say for sure that she'd be against the government regulating a woman's body. She spoke out about that issue quite clearly."[21] [edit] See also[edit] References

[edit] Further reading

[edit] External links

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL). |

Connect with Connexions

|

|||||||||||||||||